Methods and Initializers

When you are on the dancefloor, there is nothing to do but dance.

Umberto Eco, The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana

It is time for our virtual machine to bring its nascent objects to life with behavior. That means methods and method calls. And, since they are a special kind of method, initializers too.

All of this is familiar territory from our previous jlox interpreter. What’s new in this second trip is an important optimization we’ll implement to make method calls over seven times faster than our baseline performance. But before we get to that fun, we gotta get the basic stuff working.

28 . 1Method Declarations

We can’t optimize method calls before we have method calls, and we can’t call methods without having methods to call, so we’ll start with declarations.

28 . 1 . 1Representing methods

We usually start in the compiler, but let’s knock the object model out first this time. The runtime representation for methods in clox is similar to that of jlox. Each class stores a hash table of methods. Keys are method names, and each value is an ObjClosure for the body of the method.

typedef struct {

Obj obj;

ObjString* name;

in struct ObjClass

Table methods;

} ObjClass;

A brand new class begins with an empty method table.

klass->name = name;

in newClass()

initTable(&klass->methods);

return klass;

The ObjClass struct owns the memory for this table, so when the memory manager deallocates a class, the table should be freed too.

case OBJ_CLASS: {

in freeObject()

ObjClass* klass = (ObjClass*)object; freeTable(&klass->methods);

FREE(ObjClass, object);

Speaking of memory managers, the GC needs to trace through classes into the method table. If a class is still reachable (likely through some instance), then all of its methods certainly need to stick around too.

markObject((Obj*)klass->name);

in blackenObject()

markTable(&klass->methods);

break;

We use the existing markTable() function, which traces through the key string

and value in each table entry.

Storing a class’s methods is pretty familiar coming from jlox. The different part is how that table gets populated. Our previous interpreter had access to the entire AST node for the class declaration and all of the methods it contained. At runtime, the interpreter simply walked that list of declarations.

Now every piece of information the compiler wants to shunt over to the runtime has to squeeze through the interface of a flat series of bytecode instructions. How do we take a class declaration, which can contain an arbitrarily large set of methods, and represent it as bytecode? Let’s hop over to the compiler and find out.

28 . 1 . 2Compiling method declarations

The last chapter left us with a compiler that parses classes but allows only an empty body. Now we insert a little code to compile a series of method declarations between the braces.

consume(TOKEN_LEFT_BRACE, "Expect '{' before class body.");

in classDeclaration()

while (!check(TOKEN_RIGHT_BRACE) && !check(TOKEN_EOF)) { method(); }

consume(TOKEN_RIGHT_BRACE, "Expect '}' after class body.");

Lox doesn’t have field declarations, so anything before the closing brace at the end of the class body must be a method. We stop compiling methods when we hit that final curly or if we reach the end of the file. The latter check ensures our compiler doesn’t get stuck in an infinite loop if the user accidentally forgets the closing brace.

The tricky part with compiling a class declaration is that a class may declare

any number of methods. Somehow the runtime needs to look up and bind all of

them. That would be a lot to pack into a single OP_CLASS instruction. Instead,

the bytecode we generate for a class declaration will split the process into a

series of instructions. The compiler already emits

an OP_CLASS instruction that creates a new empty ObjClass object. Then it

emits instructions to store the class in a variable with its name.

Now, for each method declaration, we emit a new OP_METHOD instruction that

adds a single method to that class. When all of the OP_METHOD instructions

have executed, we’re left with a fully formed class. While the user sees a class

declaration as a single atomic operation, the VM implements it as a series of

mutations.

To define a new method, the VM needs three things:

-

The name of the method.

-

The closure for the method body.

-

The class to bind the method to.

We’ll incrementally write the compiler code to see how those all get through to the runtime, starting here:

add after function()

static void method() { consume(TOKEN_IDENTIFIER, "Expect method name."); uint8_t constant = identifierConstant(&parser.previous); emitBytes(OP_METHOD, constant); }

Like OP_GET_PROPERTY and other instructions that need names at runtime, the

compiler adds the method name token’s lexeme to the constant table, getting back

a table index. Then we emit an OP_METHOD instruction with that index as the

operand. That’s the name. Next is the method body:

uint8_t constant = identifierConstant(&parser.previous);

in method()

FunctionType type = TYPE_FUNCTION; function(type);

emitBytes(OP_METHOD, constant);

We use the same function() helper that we wrote for compiling function

declarations. That utility function compiles the subsequent parameter list and

function body. Then it emits the code to create an ObjClosure and leave it on

top of the stack. At runtime, the VM will find the closure there.

Last is the class to bind the method to. Where can the VM find that?

Unfortunately, by the time we reach the OP_METHOD instruction, we don’t know

where it is. It could be on the stack, if the user

declared the class in a local scope. But a top-level class declaration ends up

with the ObjClass in the global variable table.

Fear not. The compiler does know the name of the class. We can capture it right after we consume its token.

consume(TOKEN_IDENTIFIER, "Expect class name.");

in classDeclaration()

Token className = parser.previous;

uint8_t nameConstant = identifierConstant(&parser.previous);

And we know that no other declaration with that name could possibly shadow the class. So we do the easy fix. Before we start binding methods, we emit whatever code is necessary to load the class back on top of the stack.

defineVariable(nameConstant);

in classDeclaration()

namedVariable(className, false);

consume(TOKEN_LEFT_BRACE, "Expect '{' before class body.");

Right before compiling the class body, we call

namedVariable(). That helper function generates code to load a variable with

the given name onto the stack. Then we compile the methods.

This means that when we execute each OP_METHOD instruction, the stack has the

method’s closure on top with the class right under it. Once we’ve reached the

end of the methods, we no longer need the class and tell the VM to pop it off

the stack.

consume(TOKEN_RIGHT_BRACE, "Expect '}' after class body.");

in classDeclaration()

emitByte(OP_POP);

}

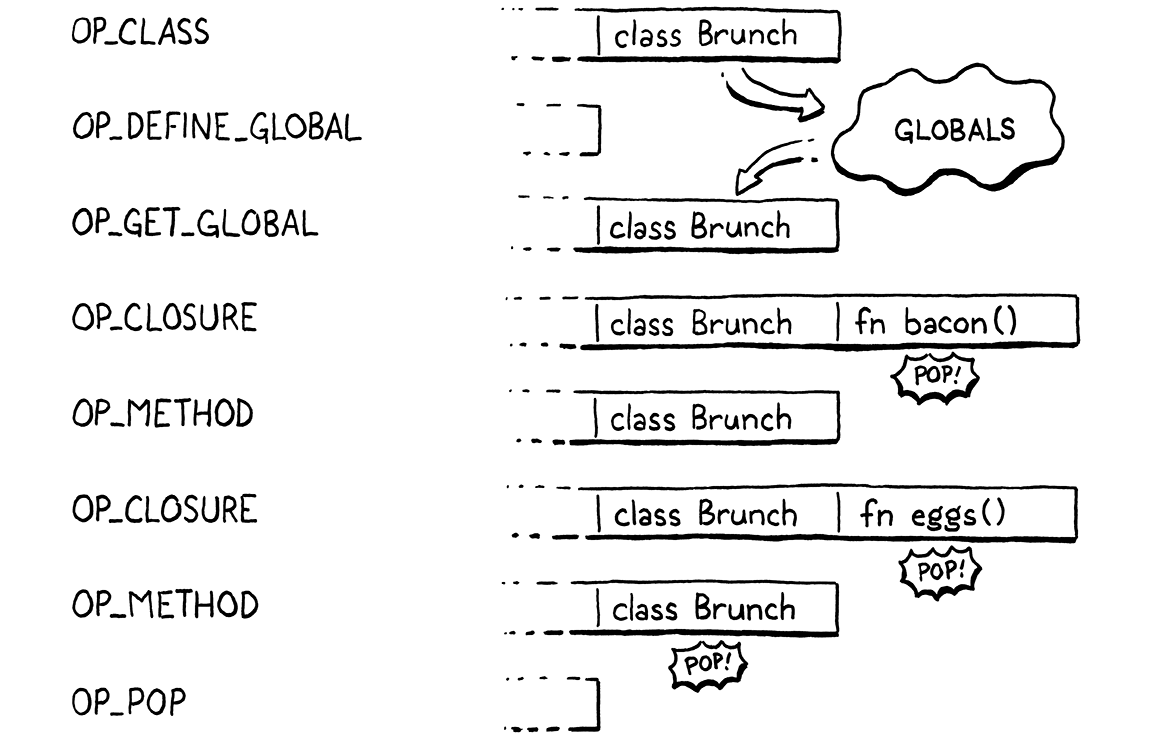

Putting all of that together, here is an example class declaration to throw at the compiler:

class Brunch { bacon() {} eggs() {} }

Given that, here is what the compiler generates and how those instructions affect the stack at runtime:

All that remains for us is to implement the runtime for that new OP_METHOD

instruction.

28 . 1 . 3Executing method declarations

First we define the opcode.

OP_CLASS,

in enum OpCode

OP_METHOD

} OpCode;

We disassemble it like other instructions that have string constant operands.

case OP_CLASS:

return constantInstruction("OP_CLASS", chunk, offset);

in disassembleInstruction()

case OP_METHOD: return constantInstruction("OP_METHOD", chunk, offset);

default:

And over in the interpreter, we add a new case too.

break;

in run()

case OP_METHOD: defineMethod(READ_STRING()); break;

}

There, we read the method name from the constant table and pass it here:

add after closeUpvalues()

static void defineMethod(ObjString* name) { Value method = peek(0); ObjClass* klass = AS_CLASS(peek(1)); tableSet(&klass->methods, name, method); pop(); }

The method closure is on top of the stack, above the class it will be bound to. We read those two stack slots and store the closure in the class’s method table. Then we pop the closure since we’re done with it.

Note that we don’t do any runtime type checking on the closure or class object.

That AS_CLASS() call is safe because the compiler itself generated the code

that causes the class to be in that stack slot. The VM trusts its own compiler.

After the series of OP_METHOD instructions is done and the OP_POP has popped

the class, we will have a class with a nicely populated method table, ready to

start doing things. The next step is pulling those methods back out and using

them.

28 . 2Method References

Most of the time, methods are accessed and immediately called, leading to this familiar syntax:

instance.method(argument);

But remember, in Lox and some other languages, those two steps are distinct and can be separated.

var closure = instance.method; closure(argument);

Since users can separate the operations, we have to implement them separately. The first step is using our existing dotted property syntax to access a method defined on the instance’s class. That should return some kind of object that the user can then call like a function.

The obvious approach is to look up the method in the class’s method table and

return the ObjClosure associated with that name. But we also need to remember

that when you access a method, this gets bound to the instance the method was

accessed from. Here’s the example from when we added methods to jlox:

class Person { sayName() { print this.name; } } var jane = Person(); jane.name = "Jane"; var method = jane.sayName; method(); // ?

This should print “Jane”, so the object returned by .sayName somehow needs to

remember the instance it was accessed from when it later gets called. In jlox,

we implemented that “memory” using the interpreter’s existing heap-allocated

Environment class, which handled all variable storage.

Our bytecode VM has a more complex architecture for storing state. Local variables and temporaries are on the stack, globals are in a hash table, and variables in closures use upvalues. That necessitates a somewhat more complex solution for tracking a method’s receiver in clox, and a new runtime type.

28 . 2 . 1Bound methods

When the user executes a method access, we’ll find the closure for that method

and wrap it in a new “bound method” object that tracks

the instance that the method was accessed from. This bound object can be called

later like a function. When invoked, the VM will do some shenanigans to wire up

this to point to the receiver inside the method’s body.

Here’s the new object type:

} ObjInstance;

add after struct ObjInstance

typedef struct { Obj obj; Value receiver; ObjClosure* method; } ObjBoundMethod;

ObjClass* newClass(ObjString* name);

It wraps the receiver and the method closure together. The receiver’s type is Value even though methods can be called only on ObjInstances. Since the VM doesn’t care what kind of receiver it has anyway, using Value means we don’t have to keep converting the pointer back to a Value when it gets passed to more general functions.

The new struct implies the usual boilerplate you’re used to by now. A new case in the object type enum:

typedef enum {

in enum ObjType

OBJ_BOUND_METHOD,

OBJ_CLASS,

A macro to check a value’s type:

#define OBJ_TYPE(value) (AS_OBJ(value)->type)

#define IS_BOUND_METHOD(value) isObjType(value, OBJ_BOUND_METHOD)

#define IS_CLASS(value) isObjType(value, OBJ_CLASS)

Another macro to cast the value to an ObjBoundMethod pointer:

#define IS_STRING(value) isObjType(value, OBJ_STRING)

#define AS_BOUND_METHOD(value) ((ObjBoundMethod*)AS_OBJ(value))

#define AS_CLASS(value) ((ObjClass*)AS_OBJ(value))

A function to create a new ObjBoundMethod:

} ObjBoundMethod;

add after struct ObjBoundMethod

ObjBoundMethod* newBoundMethod(Value receiver, ObjClosure* method);

ObjClass* newClass(ObjString* name);

And an implementation of that function here:

add after allocateObject()

ObjBoundMethod* newBoundMethod(Value receiver, ObjClosure* method) { ObjBoundMethod* bound = ALLOCATE_OBJ(ObjBoundMethod, OBJ_BOUND_METHOD); bound->receiver = receiver; bound->method = method; return bound; }

The constructor-like function simply stores the given closure and receiver. When the bound method is no longer needed, we free it.

switch (object->type) {

in freeObject()

case OBJ_BOUND_METHOD: FREE(ObjBoundMethod, object); break;

case OBJ_CLASS: {

The bound method has a couple of references, but it doesn’t own them, so it frees nothing but itself. However, those references do get traced by the garbage collector.

switch (object->type) {

in blackenObject()

case OBJ_BOUND_METHOD: { ObjBoundMethod* bound = (ObjBoundMethod*)object; markValue(bound->receiver); markObject((Obj*)bound->method); break; }

case OBJ_CLASS: {

This ensures that a handle to a method keeps the

receiver around in memory so that this can still find the object when you

invoke the handle later. We also trace the method closure.

The last operation all objects support is printing.

switch (OBJ_TYPE(value)) {

in printObject()

case OBJ_BOUND_METHOD: printFunction(AS_BOUND_METHOD(value)->method->function); break;

case OBJ_CLASS:

A bound method prints exactly the same way as a function. From the user’s perspective, a bound method is a function. It’s an object they can call. We don’t expose that the VM implements bound methods using a different object type.

Put on your party hat because we just reached a little

milestone. ObjBoundMethod is the very last runtime type to add to clox. You’ve

written your last IS_ and AS_ macros. We’re only a few chapters from the end

of the book, and we’re getting close to a complete VM.

28 . 2 . 2Accessing methods

Let’s get our new object type doing something. Methods are accessed using the

same “dot” property syntax we implemented in the last chapter. The compiler

already parses the right expressions and emits OP_GET_PROPERTY instructions

for them. The only changes we need to make are in the runtime.

When a property access instruction executes, the instance is on top of the stack. The instruction’s job is to find a field or method with the given name and replace the top of the stack with the accessed property.

The interpreter already handles fields, so we simply extend the

OP_GET_PROPERTY case with another section.

pop(); // Instance.

push(value);

break;

}

in run()

replace 2 lines

if (!bindMethod(instance->klass, name)) { return INTERPRET_RUNTIME_ERROR; } break;

}

We insert this after the code to look up a field on the receiver instance. Fields take priority over and shadow methods, so we look for a field first. If the instance does not have a field with the given property name, then the name may refer to a method.

We take the instance’s class and pass it to a new bindMethod() helper. If that

function finds a method, it places the method on the stack and returns true.

Otherwise it returns false to indicate a method with that name couldn’t be

found. Since the name also wasn’t a field, that means we have a runtime error,

which aborts the interpreter.

Here is the good stuff:

add after callValue()

static bool bindMethod(ObjClass* klass, ObjString* name) { Value method; if (!tableGet(&klass->methods, name, &method)) { runtimeError("Undefined property '%s'.", name->chars); return false; } ObjBoundMethod* bound = newBoundMethod(peek(0), AS_CLOSURE(method)); pop(); push(OBJ_VAL(bound)); return true; }

First we look for a method with the given name in the class’s method table. If we don’t find one, we report a runtime error and bail out. Otherwise, we take the method and wrap it in a new ObjBoundMethod. We grab the receiver from its home on top of the stack. Finally, we pop the instance and replace the top of the stack with the bound method.

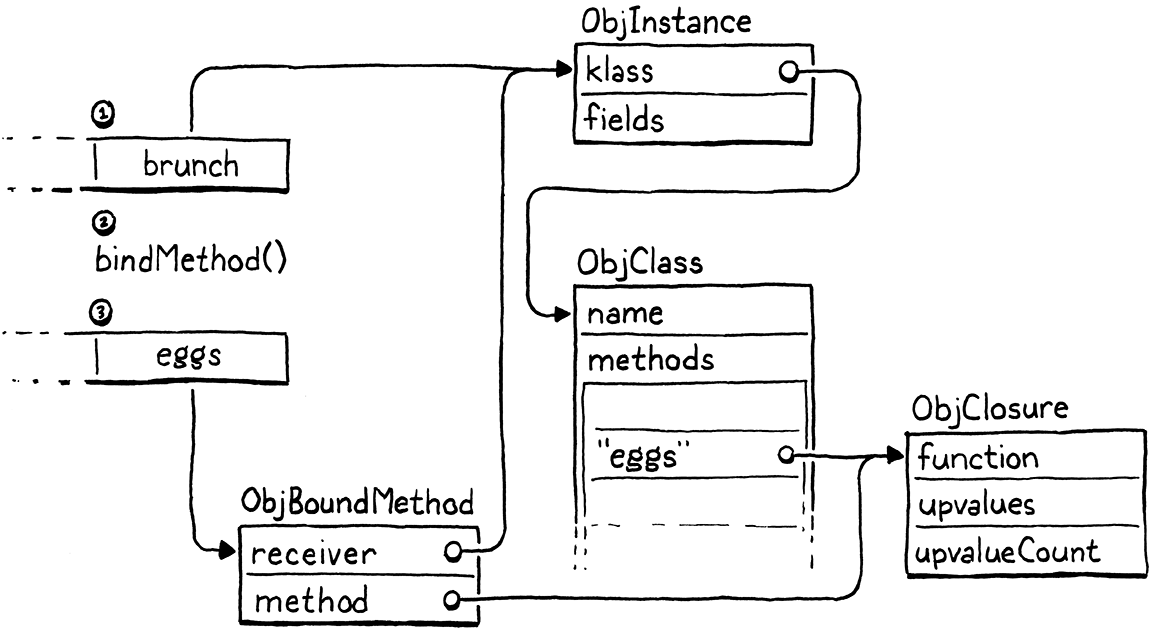

For example:

class Brunch { eggs() {} } var brunch = Brunch(); var eggs = brunch.eggs;

Here is what happens when the VM executes the bindMethod() call for the

brunch.eggs expression:

That’s a lot of machinery under the hood, but from the user’s perspective, they simply get a function that they can call.

28 . 2 . 3Calling methods

Users can declare methods on classes, access them on instances, and get bound

methods onto the stack. They just can’t do anything

useful with those bound method objects. The operation we’re missing is calling

them. Calls are implemented in callValue(), so we add a case there for the new

object type.

switch (OBJ_TYPE(callee)) {

in callValue()

case OBJ_BOUND_METHOD: { ObjBoundMethod* bound = AS_BOUND_METHOD(callee); return call(bound->method, argCount); }

case OBJ_CLASS: {

We pull the raw closure back out of the ObjBoundMethod and use the existing

call() helper to begin an invocation of that closure by pushing a CallFrame

for it onto the call stack. That’s all it takes to be able to run this Lox

program:

class Scone { topping(first, second) { print "scone with " + first + " and " + second; } } var scone = Scone(); scone.topping("berries", "cream");

That’s three big steps. We can declare, access, and invoke methods. But something is missing. We went to all that trouble to wrap the method closure in an object that binds the receiver, but when we invoke the method, we don’t use that receiver at all.

28 . 3This

The reason bound methods need to keep hold of the receiver is so that it can be

accessed inside the body of the method. Lox exposes a method’s receiver through

this expressions. It’s time for some new syntax. The lexer already treats

this as a special token type, so the first step is wiring that token up in the

parse table.

[TOKEN_SUPER] = {NULL, NULL, PREC_NONE},

replace 1 line

[TOKEN_THIS] = {this_, NULL, PREC_NONE},

[TOKEN_TRUE] = {literal, NULL, PREC_NONE},

When the parser encounters a this in prefix position, it dispatches to a new

parser function.

add after variable()

static void this_(bool canAssign) { variable(false); }

We’ll apply the same implementation technique for this in clox that we used in

jlox. We treat this as a lexically scoped local variable whose value gets

magically initialized. Compiling it like a local variable means we get a lot of

behavior for free. In particular, closures inside a method that reference this

will do the right thing and capture the receiver in an upvalue.

When the parser function is called, the this token has just been consumed and

is stored as the previous token. We call our existing variable() function

which compiles identifier expressions as variable accesses. It takes a single

Boolean parameter for whether the compiler should look for a following =

operator and parse a setter. You can’t assign to this, so we pass false to

disallow that.

The variable() function doesn’t care that this has its own token type and

isn’t an identifier. It is happy to treat the lexeme “this” as if it were a

variable name and then look it up using the existing scope resolution machinery.

Right now, that lookup will fail because we never declared a variable whose name

is “this”. It’s time to think about where the receiver should live in memory.

At least until they get captured by closures, clox stores every local variable on the VM’s stack. The compiler keeps track of which slots in the function’s stack window are owned by which local variables. If you recall, the compiler sets aside stack slot zero by declaring a local variable whose name is an empty string.

For function calls, that slot ends up holding the function being called. Since

the slot has no name, the function body never accesses it. You can guess where

this is going. For method calls, we can repurpose that slot to store the

receiver. Slot zero will store the instance that this is bound to. In order to

compile this expressions, the compiler simply needs to give the correct name

to that local variable.

local->isCaptured = false;

in initCompiler()

replace 2 lines

if (type != TYPE_FUNCTION) { local->name.start = "this"; local->name.length = 4; } else { local->name.start = ""; local->name.length = 0; }

}

We want to do this only for methods. Function declarations don’t have a this.

And, in fact, they must not declare a variable named “this”, so that if you

write a this expression inside a function declaration which is itself inside a

method, the this correctly resolves to the outer method’s receiver.

class Nested { method() { fun function() { print this; } function(); } } Nested().method();

This program should print “Nested instance”. To decide what name to give to local slot zero, the compiler needs to know whether it’s compiling a function or method declaration, so we add a new case to our FunctionType enum to distinguish methods.

TYPE_FUNCTION,

in enum FunctionType

TYPE_METHOD,

TYPE_SCRIPT

When we compile a method, we use that type.

uint8_t constant = identifierConstant(&parser.previous);

in method()

replace 1 line

FunctionType type = TYPE_METHOD;

function(type);

Now we can correctly compile references to the special “this” variable, and the

compiler will emit the right OP_GET_LOCAL instructions to access it. Closures

can even capture this and store the receiver in upvalues. Pretty cool.

Except that at runtime, the receiver isn’t actually in slot zero. The interpreter isn’t holding up its end of the bargain yet. Here is the fix:

case OBJ_BOUND_METHOD: {

ObjBoundMethod* bound = AS_BOUND_METHOD(callee);

in callValue()

vm.stackTop[-argCount - 1] = bound->receiver;

return call(bound->method, argCount);

}

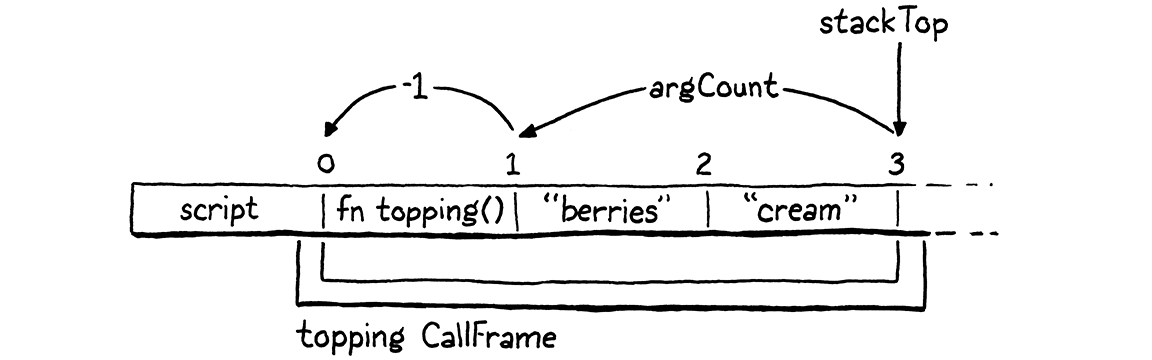

When a method is called, the top of the stack contains all of the arguments, and then just under those is the closure of the called method. That’s where slot zero in the new CallFrame will be. This line of code inserts the receiver into that slot. For example, given a method call like this:

scone.topping("berries", "cream");

We calculate the slot to store the receiver like so:

The -argCount skips past the arguments and the - 1 adjusts for the fact that

stackTop points just past the last used stack slot.

28 . 3 . 1Misusing this

Our VM now supports users correctly using this, but we also need to make

sure it properly handles users misusing this. Lox says it is a compile

error for a this expression to appear outside of the body of a method. These

two wrong uses should be caught by the compiler:

print this; // At top level. fun notMethod() { print this; // In a function. }

So how does the compiler know if it’s inside a method? The obvious answer is to look at the FunctionType of the current Compiler. We did just add an enum case there to treat methods specially. However, that wouldn’t correctly handle code like the earlier example where you are inside a function which is, itself, nested inside a method.

We could try to resolve “this” and then report an error if it wasn’t found in any of the surrounding lexical scopes. That would work, but would require us to shuffle around a bunch of code, since right now the code for resolving a variable implicitly considers it a global access if no declaration is found.

In the next chapter, we will need information about the nearest enclosing class. If we had that, we could use it here to determine if we are inside a method. So we may as well make our future selves’ lives a little easier and put that machinery in place now.

Compiler* current = NULL;

add after variable current

ClassCompiler* currentClass = NULL;

static Chunk* currentChunk() {

This module variable points to a struct representing the current, innermost class being compiled. The new type looks like this:

} Compiler;

add after struct Compiler

typedef struct ClassCompiler { struct ClassCompiler* enclosing; } ClassCompiler;

Parser parser;

Right now we store only a pointer to the ClassCompiler for the enclosing class, if any. Nesting a class declaration inside a method in some other class is an uncommon thing to do, but Lox supports it. Just like the Compiler struct, this means ClassCompiler forms a linked list from the current innermost class being compiled out through all of the enclosing classes.

If we aren’t inside any class declaration at all, the module variable

currentClass is NULL. When the compiler begins compiling a class, it pushes

a new ClassCompiler onto that implicit linked stack.

defineVariable(nameConstant);

in classDeclaration()

ClassCompiler classCompiler; classCompiler.enclosing = currentClass; currentClass = &classCompiler;

namedVariable(className, false);

The memory for the ClassCompiler struct lives right on the C stack, a handy capability we get by writing our compiler using recursive descent. At the end of the class body, we pop that compiler off the stack and restore the enclosing one.

emitByte(OP_POP);

in classDeclaration()

currentClass = currentClass->enclosing;

}

When an outermost class body ends, enclosing will be NULL, so this resets

currentClass to NULL. Thus, to see if we are inside a class—and therefore

inside a method—we simply check that module variable.

static void this_(bool canAssign) {

in this_()

if (currentClass == NULL) { error("Can't use 'this' outside of a class."); return; }

variable(false);

With that, this outside of a class is correctly forbidden. Now our methods

really feel like methods in the object-oriented sense. Accessing the receiver

lets them affect the instance you called the method on. We’re getting there!

28 . 4Instance Initializers

The reason object-oriented languages tie state and behavior together—one of the core tenets of the paradigm—is to ensure that objects are always in a valid, meaningful state. When the only way to touch an object’s state is through its methods, the methods can make sure nothing goes awry. But that presumes the object is already in a proper state. What about when it’s first created?

Object-oriented languages ensure that brand new objects are properly set up through constructors, which both produce a new instance and initialize its state. In Lox, the runtime allocates new raw instances, and a class may declare an initializer to set up any fields. Initializers work mostly like normal methods, with a few tweaks:

-

The runtime automatically invokes the initializer method whenever an instance of a class is created.

-

The caller that constructs an instance always gets the instance back after the initializer finishes, regardless of what the initializer function itself returns. The initializer method doesn’t need to explicitly return

this. -

In fact, an initializer is prohibited from returning any value at all since the value would never be seen anyway.

Now that we support methods, to add initializers, we merely need to implement those three special rules. We’ll go in order.

28 . 4 . 1Invoking initializers

First, automatically calling init() on new instances:

vm.stackTop[-argCount - 1] = OBJ_VAL(newInstance(klass));

in callValue()

Value initializer; if (tableGet(&klass->methods, vm.initString, &initializer)) { return call(AS_CLOSURE(initializer), argCount); }

return true;

After the runtime allocates the new instance, we look for an init() method on

the class. If we find one, we initiate a call to it. This pushes a new CallFrame

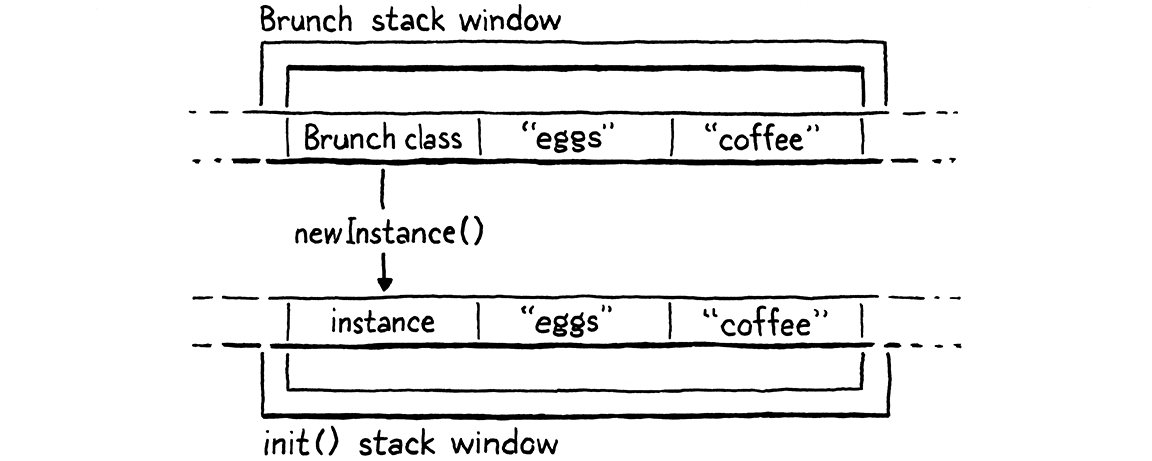

for the initializer’s closure. Say we run this program:

class Brunch { init(food, drink) {} } Brunch("eggs", "coffee");

When the VM executes the call to Brunch(), it goes like this:

Any arguments passed to the class when we called it are still sitting on the

stack above the instance. The new CallFrame for the init() method shares that

stack window, so those arguments implicitly get forwarded to the initializer.

Lox doesn’t require a class to define an initializer. If omitted, the runtime

simply returns the new uninitialized instance. However, if there is no init()

method, then it doesn’t make any sense to pass arguments to the class when

creating the instance. We make that an error.

return call(AS_CLOSURE(initializer), argCount);

in callValue()

} else if (argCount != 0) { runtimeError("Expected 0 arguments but got %d.", argCount); return false;

}

When the class does provide an initializer, we also need to ensure that the

number of arguments passed matches the initializer’s arity. Fortunately, the

call() helper does that for us already.

To call the initializer, the runtime looks up the init() method by name. We

want that to be fast since it happens every time an instance is constructed.

That means it would be good to take advantage of the string interning we’ve

already implemented. To do that, the VM creates an ObjString for “init” and

reuses it. The string lives right in the VM struct.

Table strings;

in struct VM

ObjString* initString;

ObjUpvalue* openUpvalues;

We create and intern the string when the VM boots up.

initTable(&vm.strings);

in initVM()

vm.initString = copyString("init", 4);

defineNative("clock", clockNative);

We want it to stick around, so the GC considers it a root.

markCompilerRoots();

in markRoots()

markObject((Obj*)vm.initString);

}

Look carefully. See any bug waiting to happen? No? It’s a subtle one. The

garbage collector now reads vm.initString. That field is initialized from the

result of calling copyString(). But copying a string allocates memory, which

can trigger a GC. If the collector ran at just the wrong time, it would read

vm.initString before it had been initialized. So, first we zero the field out.

initTable(&vm.strings);

in initVM()

vm.initString = NULL;

vm.initString = copyString("init", 4);

We clear the pointer when the VM shuts down since the next line will free it.

freeTable(&vm.strings);

in freeVM()

vm.initString = NULL;

freeObjects();

OK, that lets us call initializers.

28 . 4 . 2Initializer return values

The next step is ensuring that constructing an instance of a class with an

initializer always returns the new instance, and not nil or whatever the body

of the initializer returns. Right now, if a class defines an initializer, then

when an instance is constructed, the VM pushes a call to that initializer onto

the CallFrame stack. Then it just keeps on trucking.

The user’s invocation on the class to create the instance will complete whenever

that initializer method returns, and will leave on the stack whatever value the

initializer puts there. That means that unless the user takes care to put

return this; at the end of the initializer, no instance will come out. Not

very helpful.

To fix this, whenever the front end compiles an initializer method, it will emit

different bytecode at the end of the body to return this from the method

instead of the usual implicit nil most functions return. In order to do

that, the compiler needs to actually know when it is compiling an initializer.

We detect that by checking to see if the name of the method we’re compiling is

“init”.

FunctionType type = TYPE_METHOD;

in method()

if (parser.previous.length == 4 && memcmp(parser.previous.start, "init", 4) == 0) { type = TYPE_INITIALIZER; }

function(type);

We define a new function type to distinguish initializers from other methods.

TYPE_FUNCTION,

in enum FunctionType

TYPE_INITIALIZER,

TYPE_METHOD,

Whenever the compiler emits the implicit return at the end of a body, we check the type to decide whether to insert the initializer-specific behavior.

static void emitReturn() {

in emitReturn()

replace 1 line

if (current->type == TYPE_INITIALIZER) { emitBytes(OP_GET_LOCAL, 0); } else { emitByte(OP_NIL); }

emitByte(OP_RETURN);

In an initializer, instead of pushing nil onto the stack before returning,

we load slot zero, which contains the instance. This emitReturn() function is

also called when compiling a return statement without a value, so this also

correctly handles cases where the user does an early return inside the

initializer.

28 . 4 . 3Incorrect returns in initializers

The last step, the last item in our list of special features of initializers, is making it an error to try to return anything else from an initializer. Now that the compiler tracks the method type, this is straightforward.

if (match(TOKEN_SEMICOLON)) {

emitReturn();

} else {

in returnStatement()

if (current->type == TYPE_INITIALIZER) { error("Can't return a value from an initializer."); }

expression();

We report an error if a return statement in an initializer has a value. We

still go ahead and compile the value afterwards so that the compiler doesn’t get

confused by the trailing expression and report a bunch of cascaded errors.

Aside from inheritance, which we’ll get to soon, we now have a fairly full-featured class system working in clox.

class CoffeeMaker { init(coffee) { this.coffee = coffee; } brew() { print "Enjoy your cup of " + this.coffee; // No reusing the grounds! this.coffee = nil; } } var maker = CoffeeMaker("coffee and chicory"); maker.brew();

Pretty fancy for a C program that would fit on an old floppy disk.

28 . 5Optimized Invocations

Our VM correctly implements the language’s semantics for method calls and initializers. We could stop here. But the main reason we are building an entire second implementation of Lox from scratch is to execute faster than our old Java interpreter. Right now, method calls even in clox are slow.

Lox’s semantics define a method invocation as two operations—accessing the method and then calling the result. Our VM must support those as separate operations because the user can separate them. You can access a method without calling it and then invoke the bound method later. Nothing we’ve implemented so far is unnecessary.

But always executing those as separate operations has a significant cost. Every single time a Lox program accesses and invokes a method, the runtime heap allocates a new ObjBoundMethod, initializes its fields, then pulls them right back out. Later, the GC has to spend time freeing all of those ephemeral bound methods.

Most of the time, a Lox program accesses a method and then immediately calls it. The bound method is created by one bytecode instruction and then consumed by the very next one. In fact, it’s so immediate that the compiler can even textually see that it’s happening—a dotted property access followed by an opening parenthesis is most likely a method call.

Since we can recognize this pair of operations at compile time, we have the opportunity to emit a new, special instruction that performs an optimized method call.

We start in the function that compiles dotted property expressions.

if (canAssign && match(TOKEN_EQUAL)) {

expression();

emitBytes(OP_SET_PROPERTY, name);

in dot()

} else if (match(TOKEN_LEFT_PAREN)) { uint8_t argCount = argumentList(); emitBytes(OP_INVOKE, name); emitByte(argCount);

} else {

After the compiler has parsed the property name, we look for a left parenthesis.

If we match one, we switch to a new code path. There, we compile the argument

list exactly like we do when compiling a call expression. Then we emit a single

new OP_INVOKE instruction. It takes two operands:

-

The index of the property name in the constant table.

-

The number of arguments passed to the method.

In other words, this single instruction combines the operands of the

OP_GET_PROPERTY and OP_CALL instructions it replaces, in that order. It

really is a fusion of those two instructions. Let’s define it.

OP_CALL,

in enum OpCode

OP_INVOKE,

OP_CLOSURE,

And add it to the disassembler:

case OP_CALL:

return byteInstruction("OP_CALL", chunk, offset);

in disassembleInstruction()

case OP_INVOKE: return invokeInstruction("OP_INVOKE", chunk, offset);

case OP_CLOSURE: {

This is a new, special instruction format, so it needs a little custom disassembly logic.

add after constantInstruction()

static int invokeInstruction(const char* name, Chunk* chunk, int offset) { uint8_t constant = chunk->code[offset + 1]; uint8_t argCount = chunk->code[offset + 2]; printf("%-16s (%d args) %4d '", name, argCount, constant); printValue(chunk->constants.values[constant]); printf("'\n"); return offset + 3; }

We read the two operands and then print out both the method name and the argument count. Over in the interpreter’s bytecode dispatch loop is where the real action begins.

}

in run()

case OP_INVOKE: { ObjString* method = READ_STRING(); int argCount = READ_BYTE(); if (!invoke(method, argCount)) { return INTERPRET_RUNTIME_ERROR; } frame = &vm.frames[vm.frameCount - 1]; break; }

case OP_CLOSURE: {

Most of the work happens in invoke(), which we’ll get to. Here, we look up the

method name from the first operand and then read the argument count operand.

Then we hand off to invoke() to do the heavy lifting. That function returns

true if the invocation succeeds. As usual, a false return means a runtime

error occurred. We check for that here and abort the interpreter if disaster has

struck.

Finally, assuming the invocation succeeded, then there is a new CallFrame on the

stack, so we refresh our cached copy of the current frame in frame.

The interesting work happens here:

add after callValue()

static bool invoke(ObjString* name, int argCount) { Value receiver = peek(argCount); ObjInstance* instance = AS_INSTANCE(receiver); return invokeFromClass(instance->klass, name, argCount); }

First we grab the receiver off the stack. The arguments passed to the method are above it on the stack, so we peek that many slots down. Then it’s a simple matter to cast the object to an instance and invoke the method on it.

That does assume the object is an instance. As with OP_GET_PROPERTY

instructions, we also need to handle the case where a user incorrectly tries to

call a method on a value of the wrong type.

Value receiver = peek(argCount);

in invoke()

if (!IS_INSTANCE(receiver)) { runtimeError("Only instances have methods."); return false; }

ObjInstance* instance = AS_INSTANCE(receiver);

That’s a runtime error, so we report that and bail out. Otherwise, we get the instance’s class and jump over to this other new utility function:

add after callValue()

static bool invokeFromClass(ObjClass* klass, ObjString* name, int argCount) { Value method; if (!tableGet(&klass->methods, name, &method)) { runtimeError("Undefined property '%s'.", name->chars); return false; } return call(AS_CLOSURE(method), argCount); }

This function combines the logic of how the VM implements OP_GET_PROPERTY and

OP_CALL instructions, in that order. First we look up the method by name in

the class’s method table. If we don’t find one, we report that runtime error and

exit.

Otherwise, we take the method’s closure and push a call to it onto the CallFrame stack. We don’t need to heap allocate and initialize an ObjBoundMethod. In fact, we don’t even need to juggle anything on the stack. The receiver and method arguments are already right where they need to be.

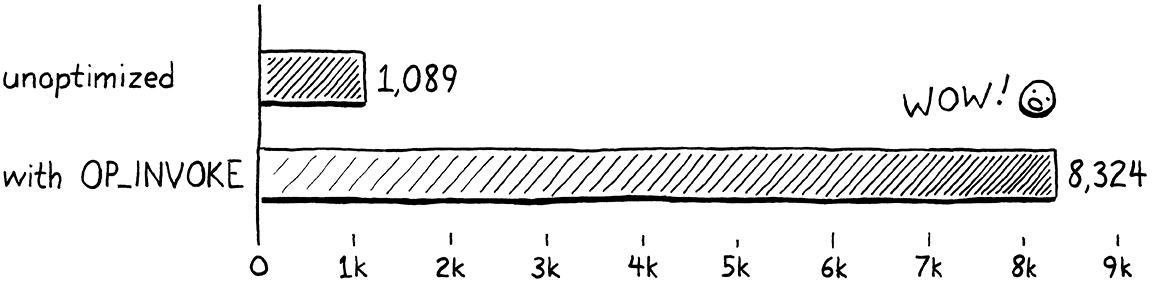

If you fire up the VM and run a little program that calls methods now, you

should see the exact same behavior as before. But, if we did our job right, the

performance should be much improved. I wrote a little microbenchmark that

does a batch of 10,000 method calls. Then it tests how many of these batches it

can execute in 10 seconds. On my computer, without the new OP_INVOKE

instruction, it got through 1,089 batches. With this new optimization, it

finished 8,324 batches in the same time. That’s 7.6 times faster, which is a

huge improvement when it comes to programming language optimization.

28 . 5 . 1Invoking fields

The fundamental creed of optimization is: “Thou shalt not break correctness.” Users like it when a language implementation gives them an answer faster, but only if it’s the right answer. Alas, our implementation of faster method invocations fails to uphold that principle:

class Oops { init() { fun f() { print "not a method"; } this.field = f; } } var oops = Oops(); oops.field();

The last line looks like a method call. The compiler thinks that it is and

dutifully emits an OP_INVOKE instruction for it. However, it’s not. What is

actually happening is a field access that returns a function which then gets

called. Right now, instead of executing that correctly, our VM reports a runtime

error when it can’t find a method named “field”.

Earlier, when we implemented OP_GET_PROPERTY, we handled both field and method

accesses. To squash this new bug, we need to do the same thing for OP_INVOKE.

ObjInstance* instance = AS_INSTANCE(receiver);

in invoke()

Value value; if (tableGet(&instance->fields, name, &value)) { vm.stackTop[-argCount - 1] = value; return callValue(value, argCount); }

return invokeFromClass(instance->klass, name, argCount);

Pretty simple fix. Before looking up a method on the instance’s class, we look

for a field with the same name. If we find a field, then we store it on the

stack in place of the receiver, under the argument list. This is how

OP_GET_PROPERTY behaves since the latter instruction executes before a

subsequent parenthesized list of arguments has been evaluated.

Then we try to call that field’s value like the callable that it hopefully is.

The callValue() helper will check the value’s type and call it as appropriate

or report a runtime error if the field’s value isn’t a callable type like a

closure.

That’s all it takes to make our optimization fully safe. We do sacrifice a little performance, unfortunately. But that’s the price you have to pay sometimes. You occasionally get frustrated by optimizations you could do if only the language wouldn’t allow some annoying corner case. But, as language implementers, we have to play the game we’re given.

The code we wrote here follows a typical pattern in optimization:

-

Recognize a common operation or sequence of operations that is performance critical. In this case, it is a method access followed by a call.

-

Add an optimized implementation of that pattern. That’s our

OP_INVOKEinstruction. -

Guard the optimized code with some conditional logic that validates that the pattern actually applies. If it does, stay on the fast path. Otherwise, fall back to a slower but more robust unoptimized behavior. Here, that means checking that we are actually calling a method and not accessing a field.

As your language work moves from getting the implementation working at all to getting it to work faster, you will find yourself spending more and more time looking for patterns like this and adding guarded optimizations for them. Full-time VM engineers spend much of their careers in this loop.

But we can stop here for now. With this, clox now supports most of the features of an object-oriented programming language, and with respectable performance.

Challenges

-

The hash table lookup to find a class’s

init()method is constant time, but still fairly slow. Implement something faster. Write a benchmark and measure the performance difference. -

In a dynamically typed language like Lox, a single callsite may invoke a variety of methods on a number of classes throughout a program’s execution. Even so, in practice, most of the time a callsite ends up calling the exact same method on the exact same class for the duration of the run. Most calls are actually not polymorphic even if the language says they can be.

How do advanced language implementations optimize based on that observation?

-

When interpreting an

OP_INVOKEinstruction, the VM has to do two hash table lookups. First, it looks for a field that could shadow a method, and only if that fails does it look for a method. The former check is rarely useful—most fields do not contain functions. But it is necessary because the language says fields and methods are accessed using the same syntax, and fields shadow methods.That is a language choice that affects the performance of our implementation. Was it the right choice? If Lox were your language, what would you do?

Design Note: Novelty Budget

I still remember the first time I wrote a tiny BASIC program on a TRS-80 and made a computer do something it hadn’t done before. It felt like a superpower. The first time I cobbled together just enough of a parser and interpreter to let me write a tiny program in my own language that made a computer do a thing was like some sort of higher-order meta-superpower. It was and remains a wonderful feeling.

I realized I could design a language that looked and behaved however I chose. It was like I’d been going to a private school that required uniforms my whole life and then one day transferred to a public school where I could wear whatever I wanted. I don’t need to use curly braces for blocks? I can use something other than an equals sign for assignment? I can do objects without classes? Multiple inheritance and multimethods? A dynamic language that overloads statically, by arity?

Naturally, I took that freedom and ran with it. I made the weirdest, most arbitrary language design decisions. Apostrophes for generics. No commas between arguments. Overload resolution that can fail at runtime. I did things differently just for difference’s sake.

This is a very fun experience that I highly recommend. We need more weird, avant-garde programming languages. I want to see more art languages. I still make oddball toy languages for fun sometimes.

However, if your goal is success where “success” is defined as a large number of users, then your priorities must be different. In that case, your primary goal is to have your language loaded into the brains of as many people as possible. That’s really hard. It takes a lot of human effort to move a language’s syntax and semantics from a computer into trillions of neurons.

Programmers are naturally conservative with their time and cautious about what languages are worth uploading into their wetware. They don’t want to waste their time on a language that ends up not being useful to them. As a language designer, your goal is thus to give them as much language power as you can with as little required learning as possible.

One natural approach is simplicity. The fewer concepts and features your language has, the less total volume of stuff there is to learn. This is one of the reasons minimal scripting languages often find success even though they aren’t as powerful as the big industrial languages—they are easier to get started with, and once they are in someone’s brain, the user wants to keep using them.

The problem with simplicity is that simply cutting features often sacrifices power and expressiveness. There is an art to finding features that punch above their weight, but often minimal languages simply do less.

There is another path that avoids much of that problem. The trick is to realize that a user doesn’t have to load your entire language into their head, just the part they don’t already have in there. As I mentioned in an earlier design note, learning is about transferring the delta between what they already know and what they need to know.

Many potential users of your language already know some other programming language. Any features your language shares with that language are essentially “free” when it comes to learning. It’s already in their head, they just have to recognize that your language does the same thing.

In other words, familiarity is another key tool to lower the adoption cost of your language. Of course, if you fully maximize that attribute, the end result is a language that is completely identical to some existing one. That’s not a recipe for success, because at that point there’s no incentive for users to switch to your language at all.

So you do need to provide some compelling differences. Some things your language can do that other languages can’t, or at least can’t do as well. I believe this is one of the fundamental balancing acts of language design: similarity to other languages lowers learning cost, while divergence raises the compelling advantages.

I think of this balancing act in terms of a novelty budget, or as Steve Klabnik calls it, a “strangeness budget”. Users have a low threshold for the total amount of new stuff they are willing to accept to learn a new language. Exceed that, and they won’t show up.

Anytime you add something new to your language that other languages don’t have, or anytime your language does something other languages do in a different way, you spend some of that budget. That’s OK—you need to spend it to make your language compelling. But your goal is to spend it wisely. For each feature or difference, ask yourself how much compelling power it adds to your language and then evaluate critically whether it pays its way. Is the change so valuable that it is worth blowing some of your novelty budget?

In practice, I find this means that you end up being pretty conservative with syntax and more adventurous with semantics. As fun as it is to put on a new change of clothes, swapping out curly braces with some other block delimiter is very unlikely to add much real power to the language, but it does spend some novelty. It’s hard for syntax differences to carry their weight.

On the other hand, new semantics can significantly increase the power of the language. Multimethods, mixins, traits, reflection, dependent types, runtime metaprogramming, etc. can radically level up what a user can do with the language.

Alas, being conservative like this is not as fun as just changing everything. But it’s up to you to decide whether you want to chase mainstream success or not in the first place. We don’t all need to be radio-friendly pop bands. If you want your language to be like free jazz or drone metal and are happy with the proportionally smaller (but likely more devoted) audience size, go for it.

Top